Is It Time for Aggregation to Get a Bit Smarter?

Posted by Colin Lambert. Last updated: November 3, 2021

Aggregation has risen in popularity over the past decade in FX markets, and shows little sign of losing its lustre. It does, however, come with challenges, not least, thanks to the rather blunt approach taken by some liquidity consumers, that LPs can face high competition and diminishing margins.

There has been extensive research on the subject, mainly targeting the “ideal” level and balance of aggregated liquidity stacks that suit both consumer and provider, but now XTX Markets has published a paper that argues liquidity consumers often overlook another aspect of their liquidity service, and therefore could aggregate a bit smarter.

“On algo desks the concept of a Smart Order Router (SOR) is generally well known,” the paper observes. “A smart order router considers multiple factors – for example price, historical impact, likelihood of fill – and then routes orders to venues accordingly.

“Aggregators are common in FX, with many technology providers having appeared over the last decade,” it continues. “However, an aggregator is not necessarily a smart order router.”

The paper takes a look at one approach for improving the output of an aggregator, mainly from the perspective of a typical regional bank, and discusses ways in which these aggregators could add more value for their clients.

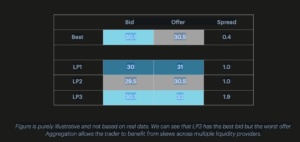

The analysis works on the premise that a typical aggregator will take in, for example, three or five LP prices and order them from best to worst.

Source: XTX Markets

This allows the client to put each order out for competition and obtain the best price available to them at any given time. “This may improve execution outcomes and unsurprisingly aggregation has become popular amongst regional banks,” the paper states.

It adds though, that a typical regional bank may have one aggregator but two separate users: the electronic desk and the voice desk. It is possible that an LP may stream different pricing to each desk, tailored to the nature of each counterparty’s flow. It continues by explaining that the way most banks work is that they will quote and win a corporate RFQ (for example a trade for 25 million EUR/USD, and will then slowly work their way out of this, by, for example, selling 1 million every 30 seconds.

“Their hope is that the spread they charge on the 25 million is more than the spread they pay on the 1 million hedging clips and the market does not move before they have hedged,” XTX says, observing that electronic and voice desks both commonly use aggregators in roughly this way, even if the former is automated and the latter will use more discretion.

Where the paper extends the discourse around aggregation, is by offering up an alternative approach for the hedging bank, based upon smarter aggregation. Noting that while the aforementioned trade is won by the LP with the best price, the paper notes it is “potentially expensive” for that party.

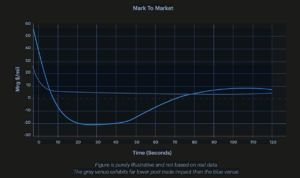

“Imagine you are a bank with 25 million to hedge,” the paper explains. “The LP with the best price is 0.1 pip better than the next LP. However, you observe that this LP causes a lot more impact (0.3 pips compared to 0.1 pips) on average in the 30 seconds post trade before you send your next child order.

“Whilst you may save 0.1 pip on the initial 1 million order, you will then lose 0.2 pips (0.3 – 0.1pip) on the 24 million balance that you have left to trade,” it adds. “The loss is almost 50x the saving.”

Source: XTX Markets

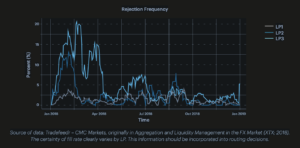

The paper also suggests looking at the impact of rejections. “Imagine a voice desk wishes to risk transfer a 20 million GBP/USD ticket just before data comes out,” it says. “LP A is 0.1 pips tighter than LP B, but LP A only has a fill rate of 75% compared to LP B with 100%. It would be sub-optimal for the aggregator to just pick the best price and ignore the potential cost of being rejected and having to re-trade at a worse price.”

All-in Aggregation Logic

The paper highlights the role of “all-in aggregation logic”, noting a handful of sophisticated regional banks route based on all-in logic. “What this means is that they weight the displayed prices by market impact and likelihood of fill,” the paper explains, providing a simple example:

Over the last 10,000 EUR/USD trades LP A has:

- a reject rate of 10%;

• a cost of rejects of 0.4 pips (as defined by the average mid-to-mid move between the timestamp of a rejected order being sent to an LP and the timestamp of that LP’s rejection);

• average market impact at 30 seconds of 0.2 pips (as defined by the average mid-to-mid move between the timestamp of an accepted order being sent to that LP and the timestamp 30 seconds later).

If LP A showed a bid of 1.20506 then subtract (10% * 0.4) and 0.2. That is 50.6 – 0.04 – 0.2 = 50.36.

The aggregator would then route on the basis of this all-in score (50.36 not 50.6), XTX explains. The LP with the best all-in score should win the trade as the all-in cost to the regional bank and client of the aggregator will have been taken into account. This means that the best displayed price will not necessarily be guaranteed to win the trade.

“This is clearly a more sensible way to route flow as it takes into account all of the potential costs to the client who uses the aggregator, rather than only one of them,” XTX says, adding,

“This feels like an interesting area to explore for aggregation software vendors. It is a crowded market and this approach might be a nice way for a vendor to stand out from the crowd.”

XTX observes that almost all aggregators have tied price logic – deciding which LP wins the trade when their prices are the same – but generally this is an incomplete solution. “The reality is that, outside top of book G3 prices, most prices are not tied,” it says. “Furthermore, the tied price logic doesn’t sufficiently capture the cost of market impact, which as described above may be the dominant cost for regional banks hedging.

“Applying all-in routing logic is actually pretty trivial for a software vendor, provided that they have the capability to generate and store these metrics,” the paper continues. “There are then some interesting UX decisions: What price should be displayed to GUI users? Should it be the all-in score or the displayed price or the displayed price of the LP with the best all-in score? In reality, this is something that is quite easy to solve in consultation with clients.”

Importantly, XTX points out that software vendors have to be careful to amass a minimum sample size of orders before applying this logic: wryly observing that a reject rate of 50% on two trades is not very meaningful and no decisions should be made on the basis of a tiny sample size.

“Applying all-in logic or asking your vendor to do so has the potential to result in meaningful improvements in hedging costs,” the paper concludes, adding, “Why not discuss the above with them and ask if it is feasible? You may also wish to get feedback from your LPs and see what perspectives they have to offer on the topic.”

The full paper can be found here.